Some fifty years ago, in September 1965, in St. Lambert, Quebec (a South Shore suburb of Montreal), the first experimental French immersion class in the public sector in Canada was launched, with a kindergarten class of twenty-six children. Since then, this model initiated by the parents of St. Lambert has spread to some 400,000 children throughout Canada, and to other parts of the world. Over time the story of the parents’ pivotal role has unfortunately been blurred to that of petitioners to McGill University, to ask them to work out an effective bilingual program for them. The parents are consistently given credit for suggesting the bilingual project, but it seems to be taken for granted that the development of the program was handed over to McGill. This is not a true reflection of what occurred.

Since there are very few parents (excluding Murielle Parkes and myself) from the original parents’ group who are available to comment, I feel it remains for someone who took an active role in developing the program to summon up her recollections, to sharpen them with the support of extensive archives, and to give as true a description as possible of how the immersion experiment came about.

The Current Problem: Acknowledging the Parents of St. Lambert

My comments are mine alone as I no longer represent any group from fifty years ago. I am motivated by an appreciation of the work of the parents and loyalty to the past. I write them in response to a basic misunderstanding of the origins of the project that has appeared lately, especially in the material for the celebration of the 50th Anniversary of the pilot project, but was also apparent in a number of earlier writings. As an example of the latter, we read: “When parents in St. Lambert began to advocate for more effective French-second-language education, Wallace Lambert and researchers from McGill University responded by developing a model for immersion education.” This comment appeared in Autumn 2011 issue of Canadian Issues/Thèmes Canadiens, published by ACS (Association for Canadian Studies) devoted to the life and work of Wallace Lambert. In that same issue, the bilingual project was frequently referred to as “Wallace Lambert’s experiment.” I was also surprised to read: “At the time when the first French immersion program was initiated in St. Lambert, parents, administrators and educators expressed serious reservations.” Could the parents of St. Lambert express serious reservations for a project they themselves developed?

One finds many other such startling statements, all of which are dismissive of the parents’ role, while granting that the idea first came from them. I don’t believe this was intentional, but perhaps it demonstrates that with time facts become distorted, especially when they don’t conform to usual expectations, and when the founders of an idea are no longer in the public eye. The similarity of names – St. Lambert and Dr. Lambert – may have added to the confusion.

Other factors may be at play, which I propose to investigate here. I do acknowledge that the contribution of the late Dr. Lambert with his rigorous four-year testing program, that began at the end of the pilot class’s first grade and not “at the kindergarten level,” was invaluable for the institutionalization of the bilingual experiment and especially for its dissemination throughout the country and beyond. However, I think it is worthwhile to take another look at the record, giving names, dates, and providing archival material in order to demonstrate what actually occurred and perhaps to learn why what is being written today does not coincide with reality. My account is not written in a straight-line fashion, but in progressively more detailed stages, which I hope will not prove confusing to the reader.

The Starting Point

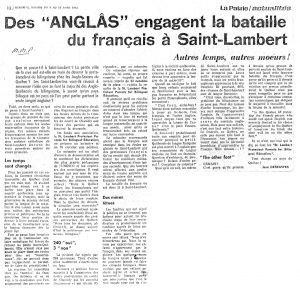

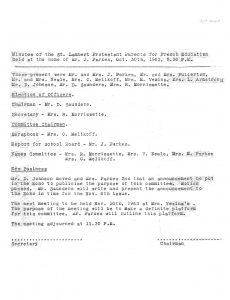

The first meeting of twelve parents interested in having their children speak French fluently occurred on October 30th, 1963 and took place at the home of Murielle and John Parkes. This group of parents named itself the “St. Lambert Protestant Parents for French Education.” The first step the members took was to elect a slate of officers, then to set up a plan to find out if there would be a significant level of community interest in their as-yet-to-be-determined model. In general terms, their proposal would be to ask the local St. Lambert Protestant School Board to provide what the parents felt was missing in St. Lambert to enable their children to become fluently bilingual. There were, at that time, several possibilities for English-speaking children to attend French school or French classes, but these options did not satisfy most English-speaking parents for a variety of reasons. There were French classes available in the Chambly County Protestant Central School Board sector (to which St. Lambert belonged), but at some distance from St. Lambert. Also, there were private schools and two French Catholic elementary schools in the city that had attracted some parents. However, this latter option was now being closed to English-speaking students for a variety of reasons that will be discussed later. The parents wanted something that had never been offered before – a high level of French within the English school system itself.

At that first meeting, there was complete agreement among the twelve members that the current method of teaching French in the English Protestant school system in Quebec was completely inadequate for what they wanted for their children, and that something needed to be done about it. There was no notion of inaugurating a totally new approach to language teaching, but only to have really effective French instruction, starting at the primary level.

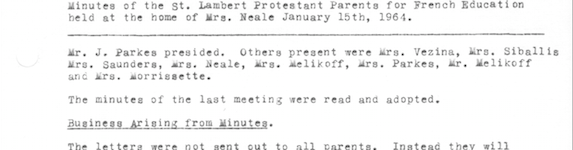

A new approach to the problem came into existence within a few weeks, when three of us – Valerie Neale, Murielle Parkes and myself – took it upon ourselves to come up with a model that would integrate both French and English in the same school program, something that to our knowledge hadn’t been done in Quebec before. We felt this solution would alleviate the problems some parents faced in placing children singly into a entirely French environment where their English language development was completely neglected. Our approach was accepted at the second meeting on November 10th, 1963, as the new goal of the membership.

A Bilingual Model

Within a few days of the first meeting, the three of us named above got together and set up priorities, in the hope that a first experimental kindergarten could be set up in the fall of 1964. First, we needed to educate ourselves on second language acquisition in general, on methods in practice around the world, and then decide what would suit our community best. In pre-computer days this was not such an easy task; we started our search for material in libraries and bookstores. At the same time, we decided that we should put our ideas into a three-pronged brief (one from each of us, according to our interests), in order to present a united front when coming before the parents, school boards, and the press. Very soon, we were leaning toward a two-language solution to our problem.

At the second meeting, we volunteered to help our newly elected chairman, David Saunders, to write an initial simplified appeal to parents to see whether they would support a bilingual approach starting at the kindergarten level. Later, when this approach was accepted, we felt it necessary to change the name of our organization from the “St. Lambert Protestant Parents for French Education” to the “St. Lambert Protestant Parents for Bilingual Education” (S.L.P.P.B.E.) to reflect this broader goal.

Our Records

At the present time, in 2018, our individual and group actions are impossible to remember in detail, though the excitement and purpose we felt are easily recalled. Fortunately, our extensive archives, put together recently into five very large binders, make it possible to retrace most of our steps. Though not complete, they record most of our actions – including our successes and failures, our frustrations, our persistence – in our quest for bilingual schooling for our children.

First Approach to Community

Under David Saunders’ chairmanship. we compiled, with some difficulty, a mailing list and sent a notice to parents of children who would be eligible for kindergarten and the first few grades and who belonged to the English Protestant sector of St. Lambert (At that time the schools in Quebec, were divided along religious lines – Roman Catholic, and everything else, grouped under Protestant.) Approximately two hundred and forty parents (or one hundred and twenty families) responded to our appeal and signed up to become members of our then “Parents for French Immersion” group. Only three dissenting replies were received, though some parents did not respond at all, either through lack of interest, or not having eligible children. It was a considerably more positive response than we had anticipated.

On receiving this community encouragement, we immediately advised the St. Lambert Protestant School Board that we would be presenting a proposal to them at their next meeting in November and would inform them of the support we were receiving for this radical change in the teaching of French.

The model we were proposing was for immersion of English-speaking children in the second language (L2) in kindergarten and the first three grades. This would create what is called a home-school language switch. It would be followed by equal time in both English and French in the remaining elementary grades, with the goal of reaching a high level of bilingualism by high school, so that both languages could be used as media of instruction there. When we presented this proposal to the local boards, we instantly saw that our idea was not only considered radical but even beyond imagining. Would this not threaten the “raison d’être” of the English language system, especially in the 1960s when language issues were at the forefront of Quebec politics. The St. Lambert Board added that they did not deal with curriculum, and that we should go to the Chambly County Central School Board with our proposal. On that board of six members, the two who represented St. Lambert proved to be the most critical of our proposal. Altogether, the Central Board showed no enthusiasm but, largely to appease the parents, they were prepared to seek outside assistance from “specialists” before making their final decision. Faced with this highly negative attitude, we knew our battle for change had begun for real and would be long and difficult.

The Parents Organize Themselves

Since the parent group was very large now and not of a manageable size to work together on a daily or weekly basis, some reorganization was inevitable. The membership naturally split up into smaller groups corresponding to the amount of commitment members were prepared to make. Soon there emerged one group of about twenty members, who were called upon when needed for projects and support, and a smaller group, a working group, of around six to eight members. This group included a nucleus of three self-appointed members – Murielle, Valerie and myself, as well as David Saunders, our chairman, and Clifford Parfett, who represented the St. Lambert Home and School Association. At various times, several others whose experience was invaluable joined this working group. The group was soon to call itself “The St. Lambert Bilingual School Study Group,” usually referred to simply as “The Study Group.” By 1966 it had replaced the other two groups. The full membership of over two hundred parents was kept informed of all developments by newsletters and by several general meetings.

The Bilingual School Study Group

The nucleus of the Study Group remained stable over the next seven or eight years (until 1972) with Murielle as secretary, Valerie as analyst and critic, and myself as chairman. During November and December of 1963, after examining the subject of bilingualism (primarily through the UNESCO Report of 1962, edited by H. H. Stern), we quickly completed a first brief explaining different aspects of our proposal. In mid-January 1964, we presented it to all members and administrators of our local and central boards and mailed it to a selection of “experts” in the field of second-language teaching in the Montreal area and in Quebec City.

The fact that we were “stay-at-home moms” gave us an advantage that we would not have had, if we had been “working moms.” We were free to get together during the daytime, to talk on the phone at length, and to visit people of interest during their working hours.

Educational Changes Occurring in Quebec

At a time when change affecting education was being examined and legislated in the Province of Quebec under the Liberal government of Jean Lesage (1960-1966), our motivation for seeking bilingualism for our children was largely apolitical. Two recognized types of motivation: instrumental (e.g. in order to obtain employment) and integrative (in order to participate in the second language culture) were represented in our membership. My primary focus was on the integrative aspect. It was revealed through testing at two later dates that the majority of parents were similarly motivated. At that time Murielle was more interested in the instrumental aspect, and Valerie in the psychological.

Generally, we thought of our proposal as an educational and cultural project, well within the capacity of young children, as demonstrated in individual cases that we were familiar with – mainly of English children in French schools. We did not think that our option should be confined to the gifted, as some suggested, or have to meet some standard of intelligence. (I actually knew a intellectually handicapped child who was trilingual.) Conscious that at least half the world is bilingual, we wanted our children not only to integrate into their own society but to have this additional tool for experiencing the diversity they would encounter in the world-at-large.

The decades of the sixties and seventies were a period of far-reaching changes in the province. Our desire for an experiment in second-language teaching in the sixties was not high on the list of priorities of the then Superintendent of Protestant Education nor, soon after, of Paul Gérin-Lajoie, the first Minister of the newly created Department of Education. The Liberals were succeeded by the Union Nationale (1966-1970) followed by a return of the Liberals, under Robert Bourassa (1970-1976); then came the victory of the Parti Québecois under René Lévesque. Throughout this period, there were constant revisions of educational and language policies, with which school boards and administrators had to contend. These, naturally, also affected the development of the immersion program – did it belong in the French or English side or did it create a new category?

“The Mothers of Immersion,” or “of Invention?”

Valerie, Murielle and I worked many hours together from 1963 to 1972, mostly just the three of us, but often with two to three other members of the Study Group. Our cohesion was facilitated by our being neighbours (Murielle and I were literally neighbours, and Valerie lived a few blocks away), who could get together regularly, often minding young children at the same time. Although I was the chairman during those years, we were interdependent and found strength in each other when the going got tough, as it frequently did. Murielle was the outgoing member; she exuded enthusiasm and, as secretary, wrote minutes and letters to our outside contacts, something she did with ease and humour. Valerie was a natural scholar with a logical and curious mind, who couldn’t abide loose thinking. She personally amassed books by the carton and would quote line and verse from them with impunity. She also had a keen sense of humour. In 1970, she wrote two university course papers — one on the history of French teaching in Quebec and the other on “The Community and the School: Why St. Lambert?” that are in our archives. I had the most experience with second-language learning and probably had the most faith in the feasibility of our proposal. I came from a bilingual and bicultural home – English and Russian – with some early exposure to French. This latter helped me handle the French aspects of our mandate; such as, attending meetings that the Quebec government was sponsoring at the end of the sixties and early seventies. (the Parent and Gendron Commissions), speaking to French teachers, choosing library and text books, attending a three-day course of study for French teachers on a new method of teaching reading in the primary grades.

We were aware that the three of us together soon became a force to be reckoned with and hoped we wouldn’t be seen as a “three-headed monster,” as we sometimes called ourselves. We had no objection to the mild name of “mothers of immersion” that appeared later on. At first, Cliff Parfett and David Saunders dealt largely with the public and the press, while we three dealt mostly with administrators, educators, and school boards. The Montreal newspapers soon became leading supporters of our proposal, at first calling it “the language bath method,” a term used in the UNESCO Report, before changing to the term “immersion.”

Who Were the Experts?

Throughout the sixties, the SLPPBE kept formal minutes of meetings, most of which have been preserved. The Study Group kept some minutes but, more often than not, kept informal notes, sometimes scribbled in pencil. We have recopied some of them for legibility for our archives. The SLPPBE’s formal correspondence has been preserved nearly intact, though a few letters or pages are missing. The two records combined, plus newspaper clippings, especially at the time of anniversaries of the project, are witness to the fact that our St. Lambert model and its first implementation were the product of St. Lambert parents and not of academics or any other groups. This will become more evident when I take a more detailed look at how events unfolded. Though we were not experts in education, in some ways we proved that educated people can themselves become experts in the face of an absence of recognized experts.

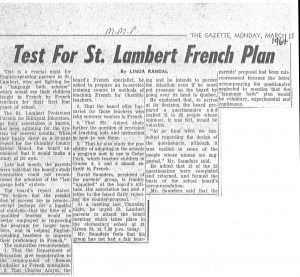

Chambly County School Board’s Questionnaire

As soon as our large parent group was formed in November 1963, we first approached the St. Lambert Board, then our regional board, the Chambly County School Board, with our proposal. We packed a number of their meetings and held heated discussions with individual members. Though most of them were resistant, some administrators were curious and prepared to listen to us. To help them with their decision, the Chambly Board decided to seek outside “guidance.” A questionnaire was prepared by the Supervisor, Mr. H. G. Greene, which was sent to twenty-two educators in the province in December 1963. The questionnaire was not shown to us in advance, and we soon found that it misrepresented our proposal: e.g. by omitting to say it was voluntary, or that English could be introduced early on (we at first suggested Grade 4, but were willing to introduce English at the Grade 2 level in order to allay fears that English would suffer). Not unexpectedly, the replies to the Board’s questionnaires were all negative on one point or another, mainly on the fate of the English language arts, a very important part of the curriculum. Fears were expressed that children would have to repeat school years unless they were particularly gifted, or would lose out on subject matter, or be frustrated by lack of understanding the teacher’s language. Their responses justified the Board’s own point of view and became the basis of their formal refusal to the parents in February 1964.

Our First Brief – January 1964

Realizing from the start that it would be difficult to get support from the Chambly County Board, we decided to get involved with more educators and to send them our own prepared material. By January 1964, we had finished our first brief, described below, which we sent to all the parents and to over twenty educators in the Province of Quebec. We even hand-delivered copies to the homes of the local and regional school board members to be sure they received them. But the Board had acted unexpectedly quickly and had beaten us in communicating with many of the same “experts.” But the response to our brief over the next few weeks proved to be more nuanced, more open, than to theirs, though still full of caveats.

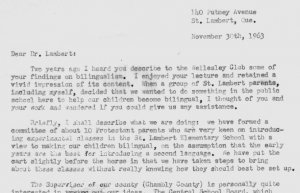

Unlike the Chambly School Board, we sent our brief to Dr. Wilder Penfield, internationally acclaimed neurosurgeon, and Dr. W. E. Lambert, social psychologist, of McGill University. We had already been in touch with Dr. Lambert in December. I had written to him, knowing that his group was involved in ongoing research on bilingualism and wanted to question him about it and to ask him to come to speak to our parents in January. Murielle and I visited him twice – in December and again in mid-January.

At our December meeting with him at McGill, he told us about some disturbing research that was going on “somewhere” that showed that bilingual students in Montreal were not doing as well in English on their S.A.T. scores as compared to American students; also, in another project, Montreal English students were performing no better in French than some students from a town in Connecticut after they had studied French for only two years. (The Montreal students had been exposed to French for eight years.) This, if true, was discouraging news. I wrote him in response to our meeting on December 20th: “No wonder you asked us why we wanted to encourage the study of French altogether.” I added: “Maybe we instinctively felt that things were so bad now that the only way to improve them was to take a new approach altogether, assuming French will not be dropped [from the curriculum].” He answered that this research was not yet completed and that we should not refer to it publicly. In general, he showed no interest in our proposal.

1964-01-15 – Brief 1 – Parkes, Melikoff and Neale

We persisted in trying to get Dr. Lambert’s attention and support and returned to see him in January to show him our first brief. He again looked very dubious and even queried; “Why in the world would you want to do that?” He suggested another option, at least for our own children, of sending them to a French school for the first few grades. We left the January meeting somewhat discouraged since our hopes had been high for his support. We did not approach him seriously again for another two years, except to ask him to suggest possible teachers for our immersion classes.

On the other hand, we did get encouragement from Dr. Penfield and some of the educators contacted, and also from the press, though not enough to influence the Board’s negative decision. We did convince the Board, in the interests of fairness, to send their questionnaire to the two professors from McGill and they did so. We were never shown how they responded, but we did receive two encouraging letters from Dr. Penfield, which I will describe below.

In March 1964, we held a meeting of all our signed-up parents, to discuss our brief and to bring them up to date on the Board’s negative verdict. It turned out to be very therapeutic for the whole group, since many had a chance to air their pent-up feelings about their own lack of facility in French, to blame the system that had been in place for many years in Quebec and in Ontario. Both Valerie and Murielle were from Ontario where Valerie had all her schooling and Murielle had a large part, arriving at Chambly County High School for Grade 9. They felt a particular absence of adequate French education. The parents, in general, were a mixture of old timers and newcomers, in a town that was growing rapidly. At that time, the population of St. Lambert was about 17,000 with an equal mix of French and English. The two linguistic groups seldom interfaced, except in sports. The parents that night made it obvious that they wished us not to give up but to forge ahead, despite the opposition of the board and the negative comments of a number of educators in regard to our brief.

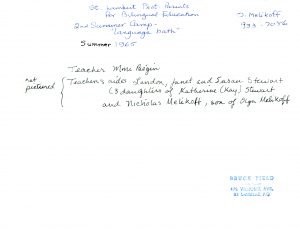

Taking the Bull by the Horns – The Parents’ Classes

Still confident in our model, even though officially rebuffed by the Board, the SLPPBE decided to take the bull by the horns and do their own demonstration of how immersion would work and, most importantly, to show how it would not harm the children. In the summer of 1964, we started immersion French classes for English children, aged four to eight, with no regard for religious affiliation. Parents became involved in the undertaking and, over a period of two and a half years, we held five teaching sessions – three in the summer and two in the winter. The summer sessions were for ten weeks (eight hours a week). The parents, working together, enrolled the children, found teachers and assistants, venues, materials, and everything required for establishing day camps in the summer, art and conversation groups in the winter. Our goal was to help the children get a start in French by using our “controversial” method – one French teacher speaking only in French to a group of anglophone children. While they were actively involved in play, the children were absorbing a new language. Some young bilingual teachers’ aides, including one of my sons, were hired to help out.

For the second session, the winter of 1964-65, we phoned Dr. Lambert and asked him if he knew of any potential teachers as they were hard to find. He suggested that a certain teacher recently arrived from France, Mme. Evelyne Billey might be available as an art teacher, and, fortunately, she was able to accept our offer. Since the local school board would not rent us space, our first class was held in the St. Lambert Baptist Church, the second in a Catholic school, and finally the third in Margaret Pendlebury School, our local Protestant elementary school that was soon to house the first official immersion kindergarten class.

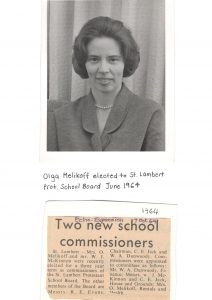

Representing SLPPbe on the St. Lambert School Board

Along with planning our parent-run classes (later visited and acknowledged as effective by Mr. C. Amyot, French specialist of the Chambly County Board), we decided to use further pressure tactics – getting a member on to the local St. Lambert School Board, in order to have someone on the inside track. In June of 1964 I was elected by acclamation for a three-year term. This position on the St. Lambert School Board gave me the opportunity to keep the SLPPBE’s agenda at the forefront of theirs.

Along with planning our parent-run classes (later visited and acknowledged as effective by Mr. C. Amyot, French specialist of the Chambly County Board), we decided to use further pressure tactics – getting a member on to the local St. Lambert School Board, in order to have someone on the inside track. In June of 1964 I was elected by acclamation for a three-year term. This position on the St. Lambert School Board gave me the opportunity to keep the SLPPBE’s agenda at the forefront of theirs.

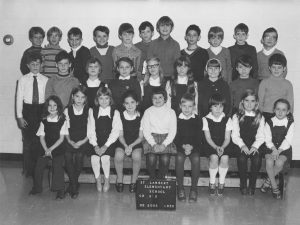

St. Lambert Board Relents: the First Immersion Kindergarten Begins – 1965

After enormous effort and pressure on the part of our membership over a period of nearly two years, the two boards involved – the St. Lambert School Board and the parent Chambly County Protestant Regional School Board – relented under the pressure and agreed to start one experimental kindergarten class in September 1965. They reasoned that one year could not do too much harm and besides, kindergarten wasn’t then compulsory in the province. They had no prospects for any kind of testing of results and expected the parents to feel responsible if the project didn’t live up to expectations. We encouraged Mme. Billey to become the first kindergarten teacher. She proved to be just the right person to inaugurate the pilot class. She went on to become a leading teacher for thirty years and at one time was the principal of St. Lambert Elementary School, to which the immersion classes moved in 1968. [She was later known as Mme. Billey-Lichon.] Murielle’s daughter and my son were among the lucky twenty-six pupils who managed to enrol just in time on the first and only registration day. (Valerie’s youngest daughter was enrolled two years later along with Murielle’s third child.) No selection was made for acceptance; it was simply first come, first served.

Our Second Brief – 1 December 1965

Because the Board would not commit to more than one experimental kindergarten that year (1965-66) or to continuing the experiment beyond kindergarten, we felt we had to significantly increase our support base and appeal to higher levels of government, assuming that would help. In an effort to attract the attention of the Department of Education in a more concrete way (their response to our first brief was minimal – simply an acknowledgement of receipt), I wrote a second brief in December 1965, addressed to the then Minister of Education, the Honourable Paul Gérin-Lajoie. The brief was first studied, then endorsed by four South Shore educational groups. In it we struck a new and more comprehensive note, asking for a formal bilingual school for St. Lambert, encompassing both Protestants and Catholics, and with a testing program to monitor it. We wrote:

There should be observation and testing all along the line to determine the effect of the second language on the total progress of the child. …

The results of a professionally-planned project, carefully recorded by experts from the field of higher education, would help parents to decide in future whether their children should begin on a bilingual curriculum. It is an option which should be available in this province, but, unlike other options, belongs at the very beginning of the primary level rather than at the high school level.

In order to emphasize the uniqueness of what we were requesting, i.e. a separate bilingual school, we explained:

Results achieved by English pupils in a French School, with a curriculum not adapted to meet their needs, have varied from success to failure. Individual experiments have often ended too soon, and no records have been kept.

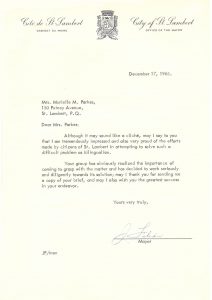

Because of an ever-growing demand for immersion on the South Shore, we wanted access to immersion to be extended to a broader community than just St. Lambert and to be open to Catholics as well as Protestants. We asked for a testing program to evaluate the effects on the children’s general level of development. This was largely as an insurance plan, and not because we had any real doubts about the outcome. It turned out that the scope of our request addressed to Mr. Gérin-Lajoie was so far-reaching that progress on a smaller scale of the already existing pilot project was made all the easier. We received many replies to our widely circulated proposal (over sixty copies were sent out): some merely acknowledgements, but others far more encouraging than after our first brief of 1964. Among the noteworthy responses was one from Mr. Pierre Laporte, then Minister of Cultural Affairs in Quebec. He personally dropped in at Murielle’s home, only about eight houses away from his own, to express his support informally. He also wrote us formally and included a copy of his letter to his colleague:

Some response to our brief included questions that required answers from the Study Group; other responders wanted to be kept informed of our progress. Katherine (Kay) Stewart, from the St. Francis Catholic PTA, was the one who was mainly in touch with the Catholic educators and St. Joseph Teachers College in Montreal, as well as with her acquaintance, Mrs. Gertrude Laing, of the Royal Commission on Bilingualism and Biculturalism. Mrs. Laing raised some important questions regarding our proposal, such as what would be the emotional effects of immersion on children as compared to placing them directly into a French school.

Mr. Paul Gallagher, of the St. Joseph Teachers College wrote to one of his colleagues that he was wary of immersion such as we were proposing. “My own reaction,” he writes, “is that, for the vast majority of pupils, this would present an unjustifiable challenge.” But he goes on to advise not to wait for permission from the Minister, but rather to go ahead and then to present him with a ‘fait accompli.’” In many ways, this had already been our mode of operation. He also suggested consulting Miss M. Buteau of St. Joseph Teachers College as well as Professor Lambert of McGill. We consulted Miss Buteau, who was to later become part of Dr. Lambert’s team of doctoral students involved in his testing program. Mr. Gallagher had at least a partial change of heart and, in response to a long letter I sent him, wrote: “I do hope your project gets off the ground well, that you get the kind of support you want and need, and that observations such as mine do not serve to dampen either your enthusiasm or your very obvious competence to push ahead.”

PDF – 1966-02-24 – Letter from OM to Paul Gallagher

From our two McGill contacts we also received replies. Dr. Lambert wrote on December 13, 1965: “It sounds like an excellent plan to me and if I can help in any way to get the [bilingual school] project started please let me know.” This was his first letter to show any interest in getting involved in our immersion project. We quickly took advantage of this opening. Dr Penfield, from the Montreal Neurological Institute, again wrote us a warm letter saying: “I congratulate you heartily on your whole approach, your perseverance and your insight.”

Reaching Out to Dr. Lambert

Reaching out to Dr. Lambert by phone in January,1966, we learned that he would be interested in engaging in a testing program for our bilingual project, provided that funding could be found. His commitment was to develop into a four-year psycholinguistic study. This was even more than the parents had hoped for. In response to his need for funding, on March 8, 1966, the Study Group appealed to the Canadian Commission for UNESCO for $10,000 to finance the start of testing. Ultimately the funds were found elsewhere, and the long-sought permission to proceed was granted by the Department of Education in the spring of 1966. The Department said that it would take them a year to arrange for testing by their own specialists and they preferred to give a grant to McGill. The Canada Council and the Defence Research Fund provided the rest of the funding.

For the following year’s Grade I class (the twenty-six children of the immersion kindergarten) and for two projected kindergarten classes for 1966-1967, we would now have the advantage of a McGill testing program. This found favour with all concerned – the parents, the school boards, the administrators and teachers. It also meant that the invaluable Mme. Billey would be able to further share and develop her successful kindergarten expertise.

Home versus school responsibility for L2

Going back two years earlier, to January 1964, when Murielle and I visited Dr. Lambert for the second time and when she visited Dr. Penfield for the first and only time (illness in the family prevented me from joining her), we found both professors were skeptical about our proposed community immersion model. At that time Dr. Lambert, who had a bilingual and bicultural home as a result of having a French wife, suggested that the best thing we could do was to put our children in French school for a few primary grades. Had his children followed that model, their French would continue to be reinforced at home on changing to an English school. Dr. Penfield gave fatherly advice and encouragement based on individual family solutions. As an example, he explained how, in a friend’s house, the upstairs was reserved for one language and the downstairs for the other. This was an in-house model that suggested separate venues for separate languages, and involved a bilingual person in the home. Neither of these suggestions could meet our needs as a community, especially since the French schools had shut their doors to us. However, we were encouraged by Dr. Penfield’s insistence on an early start, as it reinforced our proposed model.

At that point in time, the two professors were not seeing a lack of bilingualism as a community problem that called for community solutions, but as an individual family problem. However, very soon after his meeting with Murielle, Dr. Penfield responded very positively to our first brief that was based on a community solution. In his letter to us of March 11, 1964, Dr. Penfield wrote: “The really completely bilingual people have their parents to thank more often than they have the planning of educators.” This was the reality of the 1960s that we were out to change. Dr Lambert became interested in our project only after our second brief in late 1965.

It is not uncommon for people to favour their own experiences, assuming they were successful ones, as did the McGill professors, and as I too was inclined to do when examining my motivation for embracing early immersion. My husband, André, who migrated to Canada from France in 1949, and I had placed our first two children in totally French schools – the first son going to a private convent school in St. Lambert and the second to the local public French Catholic elementary school. I was somewhat concerned about their English language development and wondered if there could be a more efficient way to produce the balanced bilingualism that we were seeking, by having both languages advance together. It seemed evident that this would require a preliminary emphasis on L2, in order to create more of a balance in the use of the two languages and to take advantage of young children’s apparent natural advantage in language learning, as advanced by Dr. Penfield. In my family, later routes to bilingualism were also successful, but they were individual routes and not ones that could be replicated for populations of students.

I myself had learned rudimentary French, enough to introduce me into the French-speaking world, when my mother hired a French-Canadian girl to help in the home. I was six years old at the time and I remember that I wanted to communicate with her. It didn’t take me long (about three months) to catch on to her language and to gradually respond in kind. The five years of French I subsequently received in English elementary school in Montreal [Grades 3 through 7] added practically nothing to my growing knowledge from sources outside of school. After further years of diversified schooling in Montreal and in the United States, it became apparent to me that something was very wrong with the way we were being taught the second language in Quebec and, for that matter, in the rest of Canada. Instruction was mostly based on verb drills and translation, with almost no oral experience, more like learning Latin. My English friends acquired very little in the way of fluency, although they had all passed their provincial exams in French at the end of their schooling. This was certainly a cause for concern: so much classroom time spent unproductively.

Although I majored in French at Wellesley College and had the advantage there of two years of Russian classes with Vladimir Nabokov, on top of my home experience, I never did reach a level of balanced bilingualism with either language. Maybe one of the reasons was that I never had much oral practice. Though not reaching this goal, I do feel I benefitted greatly from a lower level. It enabled me to move and be in a sympathy with two other language groups. I agree with those who believe that balanced bilingualism should be the goal of language learning, but for that to be reached, all the language skills – listening, speaking, reading and writing – need to be mastered. It seems obvious that a school setting can provide more of this mastery to large groups of children than can individual families. Whatever the goal – balanced or functional bilingualism, the method – early or late immersion, or simply improved core programs, a prime factor for success is a positive attitude and positive motivation. Without these, any program can be ineffective. This motivation can easily be found in immersion classes, where the child wants to understand the teacher. This is sometimes called the “mother’s method.” In later learning, motivation is much more complex.

A Second Look at Our First Brief – January 1964

As a result of my language experience, I was very responsive to a phone call in October 1963 from a parent in St. Lambert, Ruth Morrissette, who, like myself, had placed children in French schools. She suggested getting together to look at ways to attain fluency in French within the English Protestant system. Her phone call to myself and to others resulted in that first meeting in October, 1963. It took no time at all for us to swing into action, as I explained above. Putting our thoughts down in writing in the form of a brief was a crucial first step in creating our immersion project, regardless of the incompleteness of our presentation, as it reached a wide audience and extended the immersion conversation. The full text of the 1st brief can be found above [1964-1-15]. The reaction to the brief was very guarded, except in the case of Dr. Penfield, who wrote us a long, encouraging letter [1964-03-11]. His last sentence was that of a visionary: “With best wishes for your project, and hoping that you will get away with it – we need an example of this sort in the Province of Quebec and in Canada.”

PDF – 1964-03-11 – Complete letter from Dr Penfield

We forwarded this letter, which also endorsed a private initiative in early bilingual education in Montreal, to the Chambly Board, but it failed to change their minds. At that point we felt very much left to our own devices. We decided to set up our own immersion classes that summer (1964) to demonstrate our method. I think this initiative, our most daring to date, was critical in eventually turning the tide in our favour since the classes engendered even further interest in the community and confirmed that we were really serious.

Another Look at the Second Brief – December 1965

Because our language classes and the launching of the first experimental kindergarten class quickly found resonance beyond the borders of St. Lambert and extended to the broader South Shore area, we decided, in December 1965, to send our second, more ambitious brief called “А Proposal for the Creation of a Bilingual School in the City of St. Lambert,” It was thought that a single bilingual school would accommodate the growing interest and desires of English Catholic parents and make it easier to find teachers, to exchange students and curricula. It was hoped that French students would be included in time, if not in the beginning.

As a result of work on this proposal, Kay Stewart of the Catholic PTA, joined our Study Group and continued to press for the immersion option with the Catholic School Board, even after they had rejected it. At first they showed interest but subsequently decided against it because they had both French and English schools within their jurisdiction and would be in a position to experiment on their own, if and when they saw fit. Kay was to write a pamphlet called “Bilingualism Without Tears” for the benefit of parents facing the new conditions that the immersion program imposed, although she herself had no young children who could benefit from her efforts. (Her children who were older had all been to French schools.) Few of our parents were French-speaking and they often wondered how they would help their children with homework and other potential problems. Kay’s pamphlet gave them useful advice.

The Role of Dr. W.E. Lambert After the Second Brief

In the early months of 1966, after the distribution of our second brief, we again approached Dr. Lambert, this time asking him to consider participating in the testing program we were advocating for our existing immersion program and the potentially expanded program suggested in the brief. He later told us that the first thing he did, after receiving our request, was to contact Dr. Penfield – to discuss with him what the possible neurological effects would be as a result of pursuing our immersion model. With Dr. Penfield’s encouragement, Dr. Lambert accepted the first formal invitation issued by the Chambly County School Board in May 1966. For us, this meant we finally had a foot in the door that would now be very difficult to remove. Parents and teachers were relieved at the news, since the acceptance of the program only one year at a time, as an experiment, was distressing to both groups.

The first battery of tests on four groups of children – the pilot class, two English classes (one local, the other from Westmount, Quebec, and one local French control group – was given in the spring of 1967. Preliminary visits to parents and IQ testing of the children to ensure equitable control groups were done by the fall of 1966. It turned out that our proposal for a distinct bilingual school in St. Lambert embracing the whole community would have to remain a distant goal. However, it did contribute to putting the continuation of the experiment in St. Lambert on a more solid footing. This prospect received a lot of publicity in the press.

Dr. Lambert’s results over each succeeding year were made available to us as they came out. Although the first year’s results were somewhat ambiguous, they proved to be increasingly positive the following years – for both English and French language development, mathematics, and some psycholinguistic measures. The parents nervously examined every statistic and breathed sighs of relief at the turn they were taking. Additionally, in Grade V, the pilot class and two follow-up classes were tested for attitudes toward speakers of L2, as were the parents, and the results proved highly positive. Motivation continued to be of the integrative type. Among the children, Dr. Lambert saw the makings of “a new type of Canadian.”

Spread of the Immersion Program

Word spread and other school boards were inundated with parents’ requests for experiments similar to ours. This resulted in the rapid expansion of the program both on the South Shore and in the Montreal region. The Study Group was invited to speak at various schools, first locally and then on the island of Montreal – Westmount, Notre Dame de Grâce, and the West Island. At these meetings we explained our experience to date (leaving out some of the heartaches), brought recordings of the children’s voices, answered the parents’ many questions as best we could, and described the results from McGill as they came out. Dr. Lambert’s partner for the first year of testing was a charming Irishman, Father J. MacNamara, who was involved in immersion studies in Ireland and to whom we were introduced at a luncheon arranged for us by Dr. Lambert.

PDF – 1968-02-05 – SLBSSG – Draft of speech for public meeting

The Development of the Program

The St. Lambert program continued to be developed year by year by the South Shore Protestant Regional School Board, the successor in 1966-67 of the Chambly County Protestant Central School Board, with constant input from the Study Group. We had now added an English specialist, Marjory Langshur, a parent of immersion children, to our ranks. In 1968, the immersion classes moved to the St. Lambert Elementary School in the centre of the city. The program, the texts, the methods used were always developed locally. There were a number of examples of curricula from which to choose: from the French Catholic system, the Toronto French School, French Protestant classes in Quebec, from France – while needing to adjust them to our own situation. The Toronto French School, which Murielle and I visited in 1966, was particularly willing to share their information. Finding teachers remained one of the most onerous tasks because of the religious affiliation requirement in the early years, and at first most teachers were obtained from France, although the pilot class did have a French-Canadian teacher for most of their Grade I.

Illustrating the newness of our method of teaching L2, one teacher from France answered an advertisement posted in France and came to Montreal, believing she would be teaching “swimming,” which the word “immersion” suggested to her! She remained here to become a successful French immersion teacher for a number of years.

PDF – 1968-10-25 – Letter to Jean-Guy Cardinal

Request for Regional Committee on the Teaching of French

When we were assured that our program was fully accepted, the Study Group insisted that the South Shore Board form a committee (on which we would be prominent) to oversee the bilingual program. As well, we wanted to be sure that all the core French programs under the South Shore Board would be re-examined and improved. We didn’t want to feel that we were leaving out the bulk of the students of the county. The committee would have representatives from among administrators, teachers, McGill University, and, of course, the Study Group. A parent from St. Bruno also joined the Committee.

From 1967 until 1970 Murielle, Valerie and I had leading roles in what was first named a “Sub-committee on French of the Chambly County School Board” and then the ”French Committee” of its successor, the South Shore Protestant Regional School Board. We met regularly to make suggestions to improve the ongoing immersion classes and to examine all levels of instruction of L2, through high school. I chaired most of these meetings in my capacity as chairman of the Study Group, while Murielle served as secretary. I realize now that our insistence on setting up these committees was one more way of keeping an eye on our immersion “baby,” to see that our program would not be diluted or endangered in any way. It appeared that the Board would be doing some of its own testing of the children, and there was always the possibility that it could arrive at different conclusions from McGill. By December 1968 there were 180 children in grades K to 3 in immersion in St. Lambert, and classes were starting up in neighbouring communities.

Dr. Lambert was present at our committee meetings several times a year to give progress reports of his testing program. He always impressed us by the thoroughness of his program and by his warm personality. He made a point of making his reports intelligible to laymen, which was much appreciated. Fortunately, the children, having nothing with which to compare their experience, thought this continual testing and the constant stream of visitors to their classroom was all a part of a normal school experience.

Dr. Lambert’s Book – 1972

Dr. Lambert’s book, The Bilingual Education of Children: The Saint Lambert Experiment, appeared In 1972 and summed up the results of his four-year testing program. He had earlier asked me to contribute something of our parents’ story, and my account, which I called: “Parents as Change Agents in Education: the St. Lambert Experiment” became an eighteen-page, Appendix A in his book. My text had been written the previous year for a course at the Université de Montréal, where I had enrolled in an M.A. program for teaching second languages. The Appendix gives a detailed account of how the parents fought for and succeeded in launching the immersion program after several years of hard work.

Recently I decided to reread my appendix and Dr. Lambert’s Introduction. I found two errors in mine, which I don’t believe affect the meaning. Since Dr. Lambert accepted my story for his book and called it “fascinating” in his Introduction, I assumed that he accepted its contents. Out of the eighteen pages in Appendix A, a description of the collaboration with him and McGill University only begins on the twelfth page.

In his Introduction, however, Dr. Lambert writes inexplicably: “After a series of discussions among parents, school administrators, and representatives of McGill’s Language Research Group the South Shore Protestant Regional School Board authorized such [an immersion] program to begin on an experimental basis in September 1965.” In fact, discussions about testing between ourselves and Dr. Lambert only started in January 1966, after the immersion kindergarten class had begun and after our second brief had been distributed. McGill’s discussions with the Chambly County Protestant Central School Board began in the spring of 1966. Final authorization to McGill from the Chambly Board came in May 1966. [The Chambly County Board was shortly after replaced by the South Shore Regional Board] There had never been any joint meetings of parents and school administrators with McGill prior to the summer of 1966 or later.

I am puzzled by the inaccuracy of Dr. Lambert’s words. Now I realize that the distortions that I found in the writings of many researchers regarding the parents’ role, which I thought had been the result of the passage of time, could be explained by this Introduction, to which they probably referred. Our parents’ group always had cordial relations with Dr. Lambert and this “slip-up” on his part cannot erase the memory of a large number of friendly meetings after 1966. However, unfortunately, a permanent false impression was created that McGill had been involved in the program from the beginning.

Dr. Lambert continued to publish his research findings in psycholinguistics and sociolinguistics up to his retirement in 1990 and even beyond. I feel he truly deserved the title of “father of bilingualism research in psychology,” as ascribed to him by researchers J. Vaid, A. Parvis, R.C. Gardner, and F. Genesee of Montreal in their tribute to him on his passing in 2009. His research opened the doors to increased research in second-language teaching in general, and in immersion in particular. Hundreds of doctoral theses and articles have now been written on immersion, and the St. Lambert experiment is usually cited as the starting point.

Closing Shop

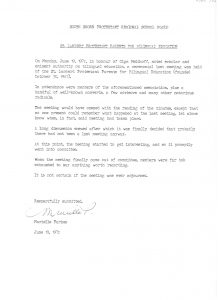

Between 1970 and 1972 the Study Group felt that it had accomplished its main goal – the initiation of an immersion program in St. Lambert, which was now spreading farther afield. We held a final meeting and celebration with old and new members on June 19, 1972. Shortly after, I left St. Lambert for Ottawa for what was to be a two-year absence from Montreal. Allan Neale, Valerie’s husband, had replaced me as a St. Lambert School Board member in 1967 and was able to keep a watchful eye on the progress of the program for a number of years to come. When the “Canadian Parents for French” was established in 1977, we felt reassured that immersion programs would be in good hands as they spread out across the country and beyond. By 1983, there were 68,315 students in immersion classes across Canada and thereafter the number was to grow exponentially. We were aware that this new approach and the new goals in language teaching would have wide repercussions on all aspects of curriculum development, and that vigilance and flexibility would always be needed as the program expanded.

Celebrating Anniversaries and Some Final Thoughts

Over the years, the main anniversaries of the first pilot class of 1965 were celebrated by the South Shore boards, and for the fiftieth anniversary, a double celebration was held – by the “Canadian Parents for French” as well as the Riverside School Board, the successor of the South Shore Regional Board. We three of the Study Group were grateful for the attention we received on these occasions. It reminded us of a decade well spent in the nineteen sixties. It was perhaps the most rewarding decade of our lives. Unfortunately, Valerie passed away in 2000, but her family continues to contribute to the cause of bilingual education. Her daughter, Ardeth (an immersion graduate), who is now a translator, has helped my family compile five thick binders of our archives over the past two years. The anniversaries were a time of remembrance but also a time to celebrate the growth of bilingual schooling and to take stock.

Murielle Parkes and I continue to reminisce about the meaning for us and our children of that decade of the 1960’s. We rejoice in the growth of bilingual education throughout the country. For Murielle, there is a little nightmarish memory from 1965 that won’t go away. She writes:

Who’d ever imagine that after devoting two years of untold hours – meeting with professionals – researching data – lobbying for French instruction – persuading sceptics – and challenging the status quo, that Olga and I almost missed getting our own two kids into the pioneer immersion class.

Who’d ever guess registration would open at 1:00?

And close at 1:05?

Fifty years later, I still shudder at what I might have done, had I been one minute late!

For me, one of the proudest moments came when, during the Winter Olympics in Vancouver in 2010, I heard young anglophone athletes from across the land being interviewed on French CBC and speaking a very presentable French – something unheard of in Canada before immersion.

I hope that our St. Lambert project will be remembered as it actually occurred, as demonstrated in our archives, and not in its revised version. This I hope for the sake of all those who were involved: the parents; the children; the teachers; Dr. Lambert and his team of graduate and undergraduate students; the successive school boards who had to deal with the difficulties of putting new programs in place under changing government directives. The Riverside School Board continues to participate in advances in second language teaching and in other fields, as do many other communities. I believe that our story of fifty years ago gives encouragement to large or small groups of people like ourselves, who work assiduously, sometimes against formidable odds, to push forward ideas they strongly believe in.

Olga Melikoff

First written: September 2016

Revised and expanded: December 2018